Mirror and tipping point to interoperable content, social, and economic graphs

A Forefront collab

This piece was originally posted to Forefront’s Mirror. Head there to read a lot more interesting writing on web3.

Interoperability is the connecting thread of the future of the social web. It’s the reason Facebook and Twitter are not so secretly working to fundamentally transform their current products. It’s the argument I’ll give for the crypto publishing platform Mirror — where this post is published — being undervalued, despite raising a round at $100M a year after launch. Interoperability is the idea that to succeed in the future, builders will design individual lego pieces rather than entire sculptures.

The world of consumer tech can feel impossible to keep up with at the moment: NFTs, social tokens, crypto wallets, AR/VR, the metaverse. Those terms describe new products and experiences and will continue to change, but interoperability is the core mechanism that brings them together. It will drive the next wave of products, including and especially science where I spend most of my time.

So I’m going to try and make interoperability as cool as a pixelated punk. I want to lay out the steps to a tipping point — where you wake up one day and the internet is almost unrecognizable from how it is now. And to make those steps as concrete as possible in this abstract world, I’ll do it through the lens of Mirror, a company with a vision that makes the opportunity of interoperability obvious.

The dream of interoperability

In essence, “interoperable” means multiple products or services can make use of the same information.

Take healthcare as an example. If I choose to switch doctors because my current one is a hack, I want my new doctor to have access to all of my medical history. It matters because it fosters competition and allows a more diverse ecosystem to evolve. My doctors should compete based on who can make me healthiest, not who has exclusive access to my data. Healthcare also illustrates the challenge interoperability has faced with privacy, but more on that later.

As Ben Thompson notes in The Web’s Missing Interoperability, interoperability was actually one of the core benefits mentioned at the start of the last wave of consumer tech, what many refer to as Web2.0. But we didn’t get interoperability from the big Web2 giants of Facebook, Twitter, and the like. We got almost the exact opposite — business models built on capturing data, storing it in private databases, and charging advertisers for access to it. We are quick to point the finger at Facebook or Twitter, but blaming them is hardly different than blaming McDonalds for the rise of fast food. The system and especially consumer pressure clearly didn’t create the incentives for interoperable technology to thrive.

More than a decade later at the dawn of Web3, consumer demand for a healthier internet is growing and there are a few important data points that suggest interoperability at scale is finally possible. First, we see that the giants are exploring this space with quite a bit more energy and openness than you might expect. Twitter — via their “BlueSky” project — is very openly researching how to build an open and interoperable standard for social media. Zuckerberg has recently been talking about Facebook becoming "becoming a metaverse company."

The simple reason the social giants even consider such bold new directions is because interoperable graphs are better for creators, and creators are the scarce resource in the quickly arriving next iteration of the internet. The most valuable asset in a world of interoperable data will be the complex business relationships creators establish between their content, other creators, and their audience. Subscribers will be replaced by supporters, angel investors by angel audiences, and collaborators by co-owners. Big tech is many things but dumb isn’t one of them, and the giants realize that tapping into those flows of money is where the trillions will be made in the future.

To be clear, it’s hard to imagine how the transition to interoperability actually happens at these existing giants. While they have been building lots of new features in line with the creator-centric strategy above — tipping, subscriptions, funding for creators, better business tools — only time will tell whether they’ll be able to execute the dramatic shifts they are pretty openly exploring.

The next question after “is it possible?” is “why should we care?” What would happen if Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and the rest all opened up their vast databases? What new types of products could we imagine getting as creators and consumers from a more interoperable world? Just a few examples to paint a picture:

For creators:

Publish anywhere. No matter where you publish or who you collaborate with, it is connected to your unique ID and distributed to your followers.

Auto-updated profiles. Rather than manually building a LinkTree of your various projects, simply put in your universal creator ID and one is populated and updated automatically.

For consumers:

Focus Twitter. Discover a version of Twitter which pulls in everyone you follow and their content, but in a single daily digest rather than a time-sucking feed. Ready to dive back into the “normal” app? That’s fine too - these apps live in parallel and have all of the same content.

Follow everywhere. Love Taylor Swift? Follow her across all of her accounts with one click.

Interoperability at scale is possible, and it can enable a healthier and more diverse product ecosystem. As As Jarrod Dicker notes, it remains to be seen whether Web2 will still exist in the future as a parallel to Web3. But it’s clear Web3 is coming, and ultimately whether it is a full replacement will come down to what we as creators and consumers value from our media. So the next step is to take a look at the changing preferences and pressures that are starting to allow interoperability to become mainstream.

Substack and Web2.5

Money talks, and building your own business as a creator has traditionally been difficult. It requires stacking a number of different building blocks on top of each other — content creation, distribution, revenue generation, admin, and so on. The cost of integrating or coordinating those different blocks has been prohibitively difficult for individuals or small groups of creators, which is why they have written for the New York Times, sung for Sony records, and acted for Disney.

But things are changing — consumers increasingly prefer to build trust with individuals or small groups. Packy put it best in “Power to the Person:”

“People follow people, not companies, but companies have long had the advantage because of all of the coordination it takes to build scaled products...Ben Thompson has said that media companies are the first to adapt to a new paradigm shift because of the relative simplicity of their products. They require very little coordination among parties, just the ability to capture and distribute one person’s thoughts, images, or dance moves.”

The media boats that first floated across Web2 moats were the Substacks and Patreons. They are the first major media networks to build huge businesses by optimizing for creator success rather than consumer engagement. They are still fully vertical — they own the content and distribution — but creators can theoretically download the emails of their audience to take it with them.

The reason I call this Web2.5 is because the Substacks and Patreons are open but not interoperable. There’s nothing stopping me from downloading my Substack subscribers and posts and manually moving to a new platform. The data is accessible but not interoperable, and that makes all the difference when it comes to building the internet of tomorrow.

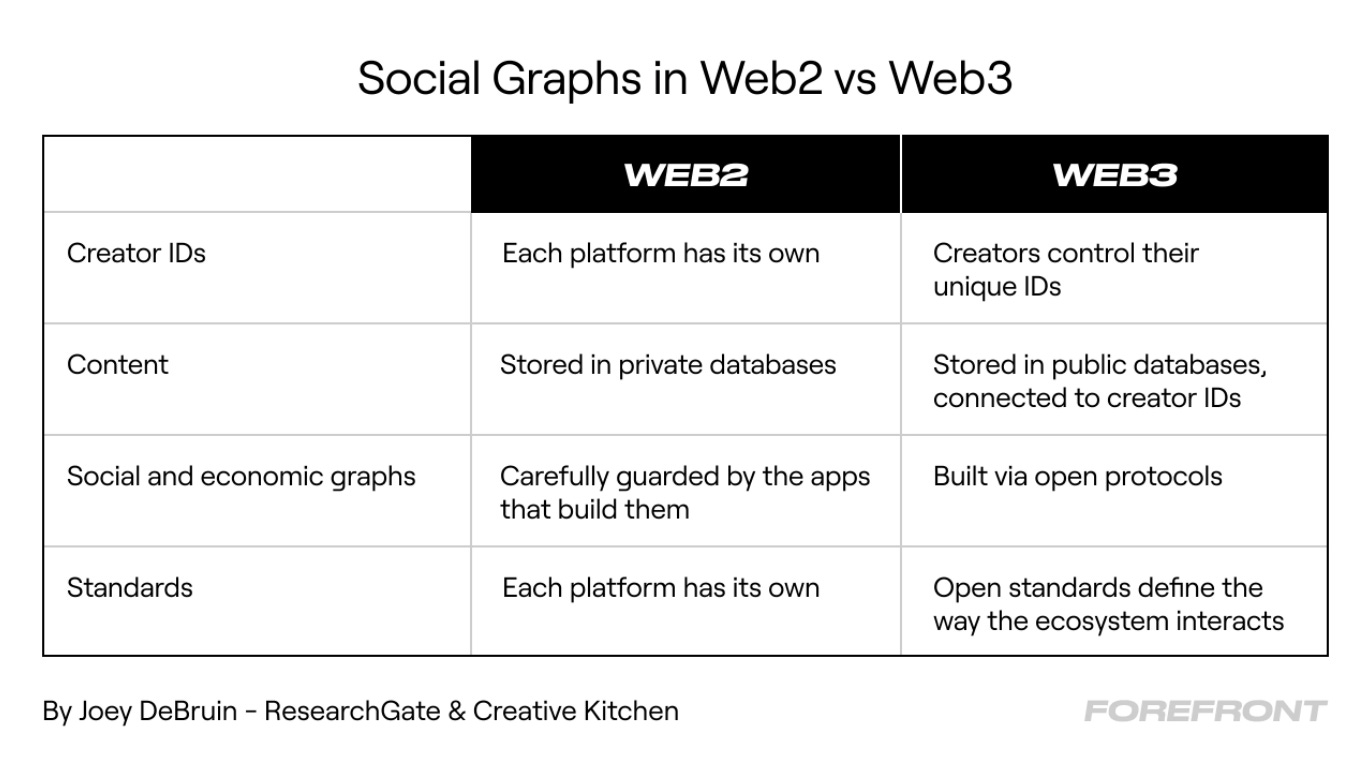

Social graphs in Web2 vs Web3 - a side by side comparison

So if interoperability is possible, exciting, and we see early signs of it happening, then what would true interoperability in media actually entail? Let’s break it down.

I admit, I’m not sure I can even imagine a future where all of the internet works in this way. We may always have fast food. But the point is that some of it will, because some of it already is. Now we’re finally ready to hold up the Mirror.

Mirror - the reflection of an interoperable future?

Mirror — the red hot “crypto Substack” which just raised >$10M at $100M from A16Z and others — is starting to look more like “crypto Kickstarter and crypto Patreon meets crypto Substack.”

Hiding behind a distracting blur of new features, Mirror’s core structure is consistent and visionary. It's a bet worth understanding on the future of interoperable content graphs, internet-native money in the form of tokens, and the dynamic new businesses that will be possible because of them.

Mirror does look a whole lot like Substack from afar - it has a publishing tool and a way to generate revenue. The most obvious difference is that it has lots of fancy crypto tools to run crowdfunds, generate NFTs for your content, and get tips and other ways to generate revenue.

On closer examination, however, we can pass it through the same criteria as above and see that it’s not far off:

A unique creator ID: I use my public Ethereum address, which I own through my private key, to publish on Mirror.

An open database of content, connected to my ID: Mirror stores content on a decentralized storage system called Arweave. If Mirror were to shut down tomorrow, I could access all of my articles by querying Arweave for the posts signed by my Ethereum address.

Open social and economic graphs: All of the important relationships built on Mirror are stored openly. Adding new members to the platform is done via their $WRITE race, a decentralized and publicly viewable vote where existing members carry more weight. When I split the proceeds of my article with another writer, or when an audience member buys an NFT in a crowdfund via my article — all of those things are signed via Ethereum addresses and stored publicly. Anyone could build apps on top of this data, for example a “Crunchbase for Creators” which shows how much funding each creator has gotten over time and from whom.

Standards: Mirror is both using and helping build open standards for the core technologies they use. They use Ethereum standards like ERC20 for fungible tokens, ERC721 for NFTs, signature standards for verifying data and so on. Some other areas like NFT sales and royalties don’t have standards yet, and Mirror is working to establish standards that can be used by others. Better standards means more adoption of those new technologies, which then benefits Mirror as the place with the best creator experience to leverage those technologies to build a business.

The key point to take away from this is that owning the content is not important to Mirror’s strategic moat. What differentiates Mirror and makes it a sticky product for creators is that it offers a number of ways to build a business that you can’t get anywhere else. Mirror dramatically lowers the coordination cost of creating a complex online business as a writer - hidden behind what looks like a content platform is actually a crowdfunding, e-commerce, and media platform all rolled up into powerful cryptographically backed tools. It’s Kickstarter, Patreon, and Substack all in one.

As a more concrete example, a film team just raised $2M to produce a documentary on Ethereum. Crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter have contribution limits of $10,000, require a bank account and only support certain jurisdictions. On the other hand, Mirror’s crypto-native crowdfunding tool had programmable contribution limits (the highest contribution was over $200k), required just a crypto wallet, and was open to anyone with an internet connection.

Patrick Rivera — an engineer at Mirror and one of the best people to follow to understand this space — calls this the “protocol economy.” Companies like Mirror own publishing and distribution for now because they have to build vertical solutions given the UX problems that are so prevalent in crypto. Being vertically integrated allows Mirror to build easy and effective onramps into the powerful protocols that will serve as their strategic moats in the future.

Crypto products that aren’t vertically integrated end up sending their users through a complex maze of different crypto apps that may have varying degrees of usability. Integrating the user journey into a single app allows crypto products to significantly improve the user experience to drive better acquisition, engagement, and retention over time. The key is to use open code and data standards to build a high-quality integrated experience.

Laying out the open structure that currently hides under Mirror’s vertically integrated solution, you can see that the shift from being a publishing company to stewarding a vibrant protocol economy has very little to do with the content itself. It’s about building developer tools for teams to use their contracts and content tools. It’s about SDKs, APIs, sub-graphs, and documentation. Their competitors will be the Stripes and Stirs of the world, not Substack. At that point, there could be multiple different apps handling publishing and distribution, all routing through Mirror’s business layer to handle things like funding, governance, revenue splits, and so on.

Could interoperability ever dry the Web2 moat?

There are a number of reasons interoperability will not happen overnight, and may never happen at scale. A few key barriers include high transaction fees, difficulty managing a crypto wallet, and scarcity of talent in the space (although all of these are rapidly improving). Not to mention privacy, security, and moderation — those topics would take an entire piece on their own but there is good reason to believe those are technical limitations which can be tackled.

The momentum to tackle these challenges can only come from an exponential UX improvement as each new interoperable product is added to the ecosystem. In other words, the network effects of the interoperable ecosystem competing with the walled-garden network effects of Web2. Using your Ethereum wallet as your Mirror account is cool, but if you can use the same wallet to log into another important product you use, the benefit scales exponentially. At a certain point, you might actively prefer to use products that allow you to use your wallet in the same way you prefer to shop with businesses that accept your credit card. That’s the tipping point.

I hope that companies like Mirror will work to push interoperability even as they focus on building onramps to crypto via vertically integrated solutions that can control the end user experience. If they can actively build seamless integrations with other open content platforms such as Audius, it could dramatically accelerate the speed of adoption of a more open internet.

The more that open platforms rely on and develop the same technology, the more they are effectively investing in each other. They become a superorganism, a swarm. As Packy put it in “Who disrupts the disruptors”, people wonder which new platform will challenge the giants, but it is the swarm of open platforms that pose the biggest threat to a real tipping point.

Platforms like Mirror have such an enormous and important challenge ahead when it comes to interoperability. But it’s not all excitement - there are a number of major challenges to a more open model. Say what you will about the job they’re doing, but centralized platforms have unique advantages to privacy and moderation that will be very difficult to build into a more decentralized web.

Amusingly, the best place I’ve found to read all about the challenges that would need to be overcome to build decentralized media platforms at massive scale is Twitter’s BlueSky project. They have curated a huge amount of content into a GitLab project on open identities, moderation privacy, monetization, and more. So perhaps we shouldn’t sleep on the incumbents after all - and if nothing else we should gain some confidence from the fact that those with all of the money are giving this topic quite a lot of attention.

Patrick and I will be hosting a hangout to discuss interoperability, Mirror, and some exciting new developments - follow me on Twitter or join the Forefront discord to grab a spot when we set the date.